Using Foxglove in VEX Robotics Competition

As the world’s largest high school robotics program, VRC brings students from across the globe to build and program robots for game-based challenges. Over the past three years, I’ve competed in VRC as captain of one of our school’s teams—we’ve made it to the World Championship twice now, and were finalists at the 2024 Ontario provincials.

Software plays a key role in VRC, often being what separates a good robot from a great one. While automation is where most of the complex problems in robotics are found—localization, path planning and motion control to name some—being able to move faster and more precisely than your competitors is well worth the effort it takes. That said, you can’t just throw advanced algorithms at your robot and expect it to zip around the field. Things rarely work on the first try, and I’ve learned through experience that visualizing your robot’s data is essential for debugging and tuning its movements.

For quite some time, our team visualized by logging sensor readings and motor commands to an SD card, then reviewing the data in Google Sheets. While this approach was simple, it had many drawbacks: importing was slow, options for visualization were limited, and organizing our data became increasingly difficult. Knowing that Google sheets wasn’t going to cut it as a long-term solution, I looked for something that offered both out-of-the-box visualization and extensibility. Foxglove was exactly what we needed, and so I developed a set of tools for integrating it into our workflow.

Foxglove-VEX Bridge

As the name implies, this program lets your robot stream to Foxglove in real-time, by reconciling the differences between how a robot can send data and how Foxglove expects it to be provided.

To get data into Foxglove, you need to host a WebSocket server implementing their subprotocol. Messaging follows the publish-subscribe model, and for each topic you’ll have to specify the encoding format (e.g., JSON, Protobuf) and schema of your data.

On the other end, to connect to your robot you need to plug a USB cable into its brain or remote control. What’s important to note is that while this connection is USB, your robot actually emulates a serial port 1. VEX layers their own protocol on top of this stack, defining the commands that can be sent to the robot and its corresponding responses (similar to an HTTP client-server interaction)2.

Now that we’ve looked at both ends of communication, let’s see how I went about connecting them. In essence, I have a robot stream data by writing messages to its standard output, which the bridge then fetches and relays to Foxglove. Messages are JSON strings consisting of a topic name and payload, and when the bridge retrieves a message, it checks whether a channel for its topic already exists. If it does, the payload is simply forwarded to Foxglove through that channel. Otherwise, the bridge advertises a new channel, providing the JSON Schema by inferring it from the payload. This design significantly simplifies end use, letting you quickly modify the structure of existing messages and add new ones.

I opted to implement the bridge in Python, so that I could focus on core logic instead of getting bogged down writing everything from scratch. Specifically, PySerial let me easily interface with serial ports and Foxglove provided a package for building servers following their spec.

VEX 2D Panel

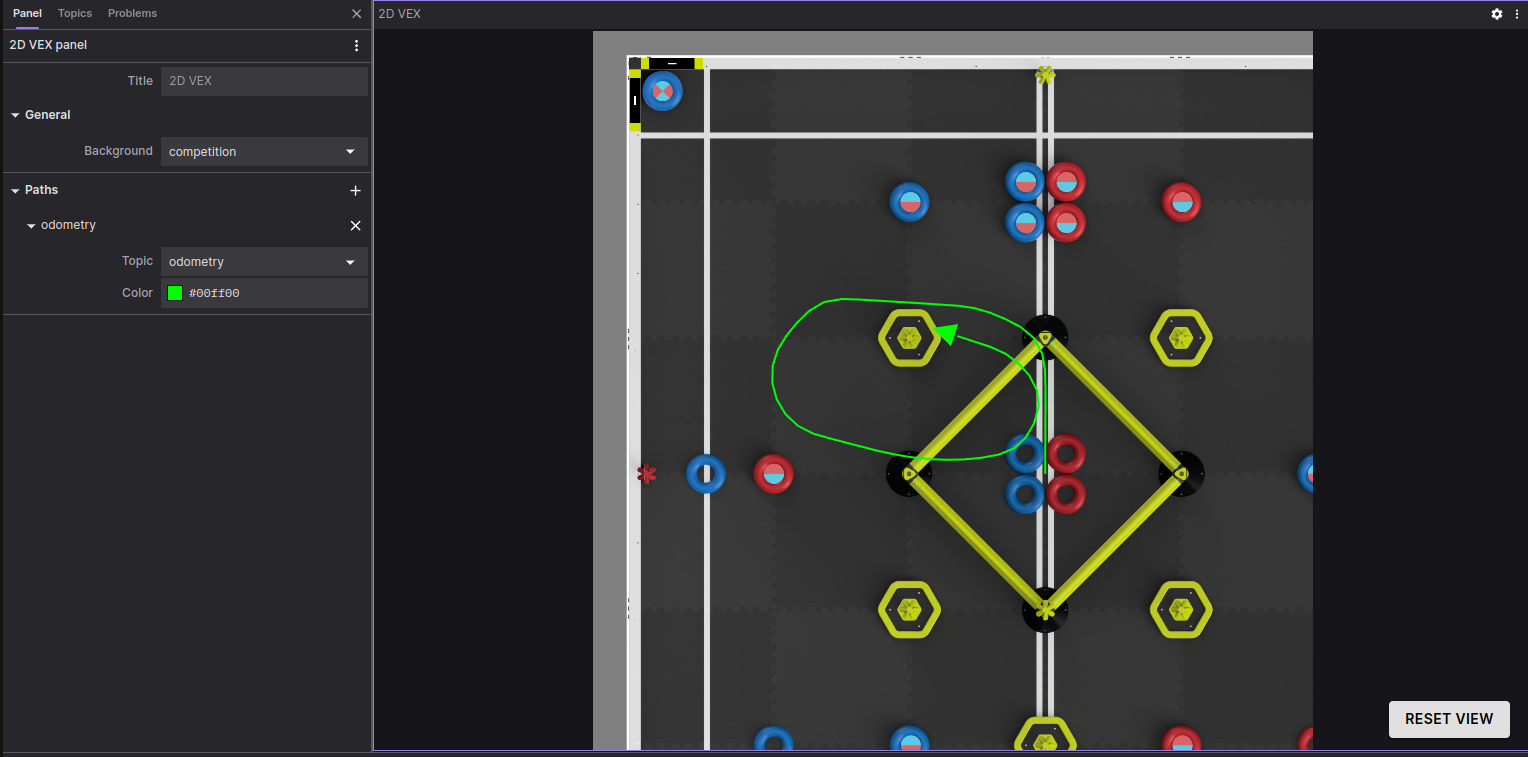

While I was now able to stream data from our robot to Foxglove, there was still some work remaining. Back when our team used Google Sheets, we were stuck with just line and scatter plots, but what we really needed was a way to visualize the robot’s pose (as a path) on top of the game field. So, I utilized Foxglove’s SDK to develop such a panel.

The panel is built with React, with its main component being an HTML canvas that renders the field and paths. Users can add or remove the paths they want to visualize through the sidebar, and they can interact with the panel by panning and zooming.

Optimizing rendering was essential since data would be streamed to the panel at a high frequency. In order to efficiently stress-test the panel during development, I wrote a server that would rapidly send mock messages to Foxglove (simulating several robots moving around). While I won’t go over all the things that helped boost performance, the biggest gains came from batching canvas stroke/fill calls and avoiding rendering off-screen poses. Also, one hack I came up with was to decrease the paths’ granularity the further you zoom out, by skipping poses that are “too close” to the previously rendered one.

Putting it all together

With these tools implemented, I had a go at programming a chassis I built earlier. This chassis’s equipped with shaft encoders and an IMU, which I used for localization and motion control. Turning in place was done using a PID controller, and moving in a straight line consisted of following a velocity profile using a feedforward-feedback controller.

By leveraging Foxglove in my workflow, I was able to quickly diagnose hardware/software problems, pick up on subtler issues, and streamline tuning the robot’s movements. What would’ve otherwise been a week of work was cut down to just two days.

Next steps

Every project has its areas for improvement, and for this one my main focus right now is optimizing the rate at which our robots can stream data to Foxglove.

When a robot writes to its stdout, the data is stored in a fixed-size buffer. This means that if data is written to the buffer faster than its read from it, the buffer will fill up, and subsequent writes will be discarded until there’s space available.

Ideally, we’d increase the rate at which the Foxglove-VEX bridge reads from the buffer, but the problem is that the bridge is hitting a bottleneck at the link between the robot and its remote control, and I’m restricted to using VEX’s hardware. Given this limitation, the only option left is to encode the data being sent more efficiently.

One idea would be to compress messages using GZIP before sending them, and then have the receiving end decompress. Since payloads are typically small and GZIP adds overhead (in the form of a header, tables, etc.), it would only make sense to GZIP a message consisting of a topic and multiple payloads. To implement this, I’d need to create a system that collects payloads for each topic into batches, which are then serialized, compressed, and written to stdout. Additionally, the Foxglove-VEX bridge would need to be refactored to handle these compressed batches.

This is just one of many approaches, but it’s a good starting point for our improvements, and a good place for me to end the blog.

-

Instead of writing their own device driver, VEX took the shortcut of having their robots emulate a serial port (for which there exist drivers). Specifics about how this is done can be found here. ↩

-

Unfortunately, VEX’s protocol is proprietary, but I was able to figure it out by untangling some open-source projects that had reverse-engineered it. ↩

Discussion and feedback